Imagine you’re going to a one-day workshop to discuss a key issue for your organisation or project. However, the problem is very ‘21st century’: it’s messy, complex and there are widely varied ideas about what the problem itself actually is! For example, “how do we create a resilient and equitable food system under the threat of climate change?”. The organisers might well have been pulling their hair out trying to come up with a format that caters for a diverse group of people who come with conflicting strong opinions, opinions they doubt, or no opinion at all.

With only one day available, how can we help participants frame and discuss this challenge? Is it possible to deliver durable new shared understandings in an immersive, inclusive, thoughtful and light-hearted way?

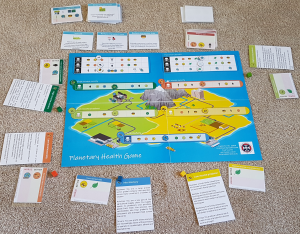

Rapid Games Design attempts to solve this problem. The approach, developed by Bruce Lankford and myself, involves small groups of participants designing (but not playing) table-top games using nothing more than the groups’ ideas, paper and pens, and games materials (e.g. counters, dice, money and the occasional plastic rhino).

During the workshop, participants build up and question their understanding of the problem as a group. The four steps are: an introduction to games designing, the game designing itself, the groups presenting their game to the whole workshop, and then a plenary workshop discussion on the topic.

The games create a common world or language which participants use to talk productively about deep issues. For example, the decision about what is in players’ power to do and what comes from a chance card stack leads to discussions about where players assume system boundaries to be, and avoids asking the question in a direct and polarising way. By comparing the various games produced participants can dive into the wide variety of perspectives on the problem which often exists. Facilitators can also reflect on the day and the games in order to then circulate a follow-up communication.

Interested? Read more on the Rapid Games Designing website.

More information on the approach can be found here and a recent paper on the application of the method, applied to several recent workshops is located here. The citation for the paper is Lankford, B.A.; Craven, J. Rapid Games Designing; Constructing a Dynamic Metaphor to Explore Complex Systems and Abstract Concepts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7200.

Based on a text by Bruce Lankford.